By Egbert Scheunemann

The following article is a revised preprint of a chapter of my book “KRETA. Eine Reise durch seine Landschaften, Geschichte und Sprache”. A book about friendship and miraculous ways of thinking. And a declaration of love.

Rebels in Crete

Probably the most spectacular action by the Greek resistance to the violent dictatorship of the colonels was the occupation of the technical college “Athens Polytechnical School” by protesting students on November 14, 1973. It was brutally shot down by the fascist junta on November 17, 1973. 22 deaths have been reported. November 17 was raised to the national day of remembrance after the end of the dictatorship.

The composer of the music for the impressive film of Costa-Gavras later became the most famous prisoner of Oropós: Míkis Theodorákis (* 1925). His biography is as depressing as it is impressive.

Mikis Theodorakis already fought as a teenager in the Greek People’s Liberation Army ΕΛΑΣ (Εθνικός Λαϊκός Απ- ελευθερωτικός Στρατός) against the Italian-German-Bulgarian fascist occupation of Greece (1941-1944) – and was tortured for the first time at the age of eighteen. During the period of the Greek civil war in 1946-1949, he fought the royalist regime on the side of the communists – and was arrested in 1947, first exiled to the island of Ikaría in the eastern Aegean, then deported to the most western island of the Cyclades, Makrónisos, and subject to severe torture. When he was released, he was close to death.

In his parents‘ house in Crete, he recovered slowly and with difficulty from the terrible abuse.

After the military coup by the right-wing colonels on April 21, 1967, Theodorákis fought as the founder of the resistance organization Patriotic Front (ΠΜ –Πατριωτικό Μέτωπο) underground against the dictatorship – and was arrested, tortured and deported to the Oropós concentration camp in August 1967. Here he became seriously ill with tuberculosis, which he almost succumbed to.

The most well-known heads of the international solidarity movement campaining for his liberation were Dimitri Shostakovich, Leonard Bernstein, Harry Belafonte, Arthur Miller, Laurence Olivier and Yves Montand (who played the role of Grigóris Lambrákis). While doing research on Greek resistance to the right-wing dictatorship, I came across a chronological list of over thirty pages of resistance actions by various anti-regime groups and regime responses. It was compiled in 1997 on the occasion of the 30th anniversary of the coup by the Athens daily newspaper Ελευθεροτυπία – the Free Press. Figures, data, facts, recorded month by month and year by year.

Rebels in Crete: Georgios Tzobanakis and Spiros Blazakis

An interesting chronology of resistance, mass demonstrations, bombings and underground political actions – and a compendium of the regime’s bloody reactions: mass arrests, short trials at military courts, torture, kidnappings, killings. One of the most touching and probably also bizarre, but nevertheless true episodes from the Greek resistance is probably the one about the two Cretan freedom fighters Giórgos Tzobanákis and Spíros Blazákis.

They fought with the left-wing rebels during the Greek Civil War between 1946 and 1949 – and in October 1949, when the civil war in Greece was actually officially over, did not surrender at all but continued their struggle underground against the restoration of the monarchy.

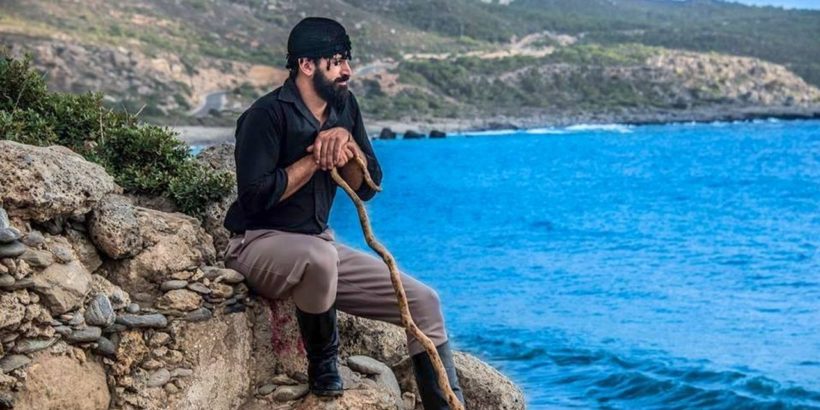

Freedom fighters in Crete

When during 1946 to 1949 the Western countries, especially the USA, supported the right-wing Greek monarchists, Geórgios Tzobanákis and Spíros Blazákis along with many other Cretan freedom fighters took up arms again to fight especially against the institutions of NATO and the United States.

Let us recall some brief historical background and connections:

- The right-wing coup leaders around Geórgios Papadópulos carried out their coup d’état according to a secret NATO plan, called Prometheus, which had been worked out for cases of a ‚communist threat‘ in any country.

- The world was in the middle of the Cold War. The Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962 was still vividly remembered. Right-wing dictatorships with the support of the United States ruled in Portugal and Spain – and soon in Chile, Argentina and almost all of South America. The Vietnam War was heading for its first climax.

- To name the secret general plan of the US-dominated NATO against ‚communist infiltration‘, “Prometheus” was sheer cynicism: Prometheus brought fire from the gods to mankind. The NATO strategy with the same name also brought some kind of fire to its victims – that of gun shoots. This misuse of the name has to be particularly bitter for the Greeks – after all, Prometheus, friend and cultural founder who had to pay bitterly for the theft of the fire, was one of their representatives, one of their gods.

Resistance in Crete

This explains why Geórgios Tzobanákis and Spíros Blazákis also opposed and above all directed attacks against institutions and the western military alliance: They cut off electricity pylons supplying the NATO missile base on Akrotíri, the small peninsula in front of the north-western Cretan city of Chaniá. They also tried an explosive attack on the base. But it failed – and Tzobanákis had to flee. He swam through the bay of Soúda at night between Akrotíri and Cape Drapanó, which is located southeast – a distance of almost twenty kilometers. When Tzobanákis‘ situation got too hot there on the following day, he swam right back the next night.

Freedom or Death!

This is the Cretan’s credo when it comes to freedom: Ελευθερία ή Θάνατος! Freedom or death! From then on, until the end of the dictatorship in 1974, Geórgios Tzobanákis and Spíros Blazákis were hunted all over Crete by police officers and soldiers, dogs and helicopters. They hid in caves and fed on grass or wild fruits when even the support from few reliable friends seemed to be too dangerous. They treated gunshot wounds with urine or lemon juice. For their capture, an astronomically high sum equivalent to 200,000 Euros was set out.

Only when the first freely elected Greek Prime Minister Konstantin Karamanlis announced an amnesty for all resistance fighters after the end of the dictatorship Geórgios Tzobanákis and Spíros Blazákis ended their struggle for freedom – after 33 years.

In Athens, they received a triumphant reception with thousands of people. But they couldn’t stand the hustle and bustle of the huge metropolis for long. After almost three decades more or less continuously living outdoors they found the tavernas in the capital of Greece were too smoky, the air too polluted and the water too chlorinated. That could, they thought, weaken the revolutionary resistance or even impair swimming performance.

Hello Jason, I have no original sources. I drew my informations about the two rebels from various press articles and other sources that I found on the Internet (including Wikipedia, etc.). If I remember correctly, I also found information in the following book (I only have the German title): Vassílios Vuidáskis: Tradition und sozialer Wandel auf der Insel Kreta (2. Auflage 1982; 1. Auflage 1977). Greetings! Egbert

Egbert – I am a Professor of terrorism studies at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies. I am related to Spyros Blazakis and keen to see if you have any documents regarding him you’d be willing to share with me.