„Freedom or death!” – The tragedy of the Arkadi Monastery in the Cretan struggle for independence in November 1866.

by Dr. Holger Czitrich Stahl.

The island of Crete is considered the cradle of European civilization. The Minoan palace culture, which the Crete visitor encounters primarily in Knossos and Festos, began around 2000 BC and ended with the conquest of Crete by the Mycenaean mainland Greeks around 1450 BC.

In the meantime, an archaeological puzzle seems to have been solved: in the 17th century BC, the palace culture suddenly collapsed at the height of its power, and only about a hundred years later did new palaces appear on the ruins, the remains of which we can see today.

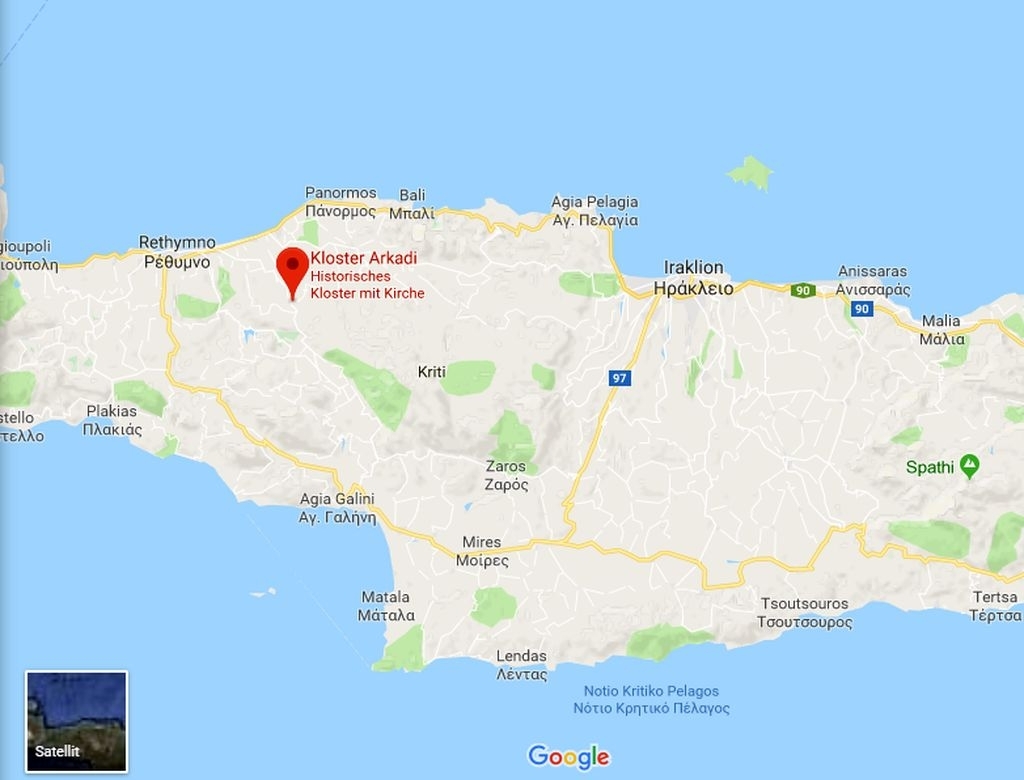

Arkadi Monastery near Rethymno.

The legendary volcanic eruption of Santorini actually took place around 1630 BC. Crete’s north was not destroyed by tsunamis but by strong earthquakes which occurred at a time of extreme tectonic activity and were also responsible for the volcanic eruption of Santorini.

Mythology also refers to Crete as the cradle of Europe, since it conveyed the message to the following generations that Zeus, born in Crete, kidnapped the Phoenician princess Europe in the shape of a bull and brought her ashore in Crete.

The legend of the Minotaur also goes back to the Mycenaean formation of hegemony. The name of the legendary King Minos must be understood as a title, not as a name.

The sea kingdom (thalassocracy) of Crete was well located for the antic seafarers on their routes between Egypt, the world of the mainland Greeks and the islands of the Aegean and, the Levant with its advanced civilization of the Phoenicians, who in turn had contact with Mesopotamia. In this respect, it served as a cultural-historical bridge between the „fertile crescent“ and the awakening Europe.

Arkadi Monastery.

This Crete, whose inhabitants were described as very proud and in certain regions such as Sfakia south of Chania even as wild, repeatedly attracted conquering hegemonic powers. Rome followed the Greek superpower. After the division of the Roman empire in AD 395, Byzantium ruled the island, which was replaced by the Arabs before 1000. After another Byzantine rule, Crete fell to Venice before, in 1669, the Ottoman Empire incorporated Crete. The Cretans always reacted with riots. These liberation actions which ended mostly in terrible tragedies, created the Cretans‘ reputation as indomitable and defiant fighters.

The Turkish (and meanwhile Egyptian) occupiers cruelly ruled with practices like public skinning, four-parting and other atrocities. Many men fled as partisans to the impassable mountains of Lefka Ori or Psiloritis, from where they carried out raids and acts of sabotage. This partisanism was a major problem for the Italian and German occupants even in the Second World War.

In 1821, mainland Greeks rose against the Sublime Porte in Istanbul. Crete also rebelled against the Ottomans.

While in 1830 a mainland Greek state was formed with the help of the European powers and Otto of Wittelsbach was appointed the first Greek king, the uprising on Crete failed.

In 1824, several hundred insurgents hid from the Ottoman troops in the Melidoni cave. These could not conquer the cave and therefore closed the entrance smoking out all the inmates until nobody was alive anymore.

England intervened to make sure that Crete was not allowed to become part of the Greek state.

In 1830, Crete fell to Egypt for eleven years before being re-annexed into the Ottoman Empire after 1840. The Cretans used every crisis for liberation actions against the increasingly ailing Sublime Porte, which was soon to be called the „sick man on the Bosporus“.

„Freedom or death!“ – This was the battle cry of the Cretan fighters.

On November 8, 1866, representatives of numerous resistance groups met for an illegal conference in the Arkadi Monastery, 23 km from Rethymnon, under the leadership of Abbot Gavriil. There were a total of abound 1,000 people on the monastery grounds including around 325 men, 250 of which armed, and more than 650 women and children.

Storks breed in the monastery garden in summer.

The Turkish Pasha resided in Rethymnon. When he received word from the illegal assembly he gave order for immediate dissolution. When the resistance fighters ignored this order an army of around 15,000 men marched from Rethymnon towards Moni Arkadi. The Turks started to occupy the monastery.

Two days later, most of the insurgents had holed up in the powder magazine. Their capture was imminent. Abbot Gavriil from Margarites and partisan leader Kostas Giamboudakis decided to act in despair. While the troops made their way to the insurgents in the powder magazine Giamboudakis held a torch at a powder keg. The magazine exploded killing more than 800 trapped insurgents and countless Ottoman soldiers. It is said that twice as many besiegers lost their lives as besieged. The few survivors were captured. The monastery was almost completely destroyed. November 8th is the Cretan National Day commemorating the tragedy of Arkadi Monastery.

However, this act of desperation did not initially lead to Crete’s freedom. It was only after British soldiers were caught between the fronts and killed during the 1895-97 uprisings that the major powers decided to act. In 1898, Crete achieved formal independence, not as part of Greece, but as an autonomous ward of the European powers England, France, Russia, Italy and Austria-Hungary with the Greek Prince George as High Commissioner. The Cretans got rid of him in 1906.

Crete’s most talented politician at the turn of the century, the liberal Eleftherios Venizelos (1864-1936), finally became the Greek Prime Minister who united Crete with the Greek state in 1913.

„Freedom or death!“ – after terrible blood sacrifices, Crete had achieved her freedom. It was the great Nikos Kazantzakis (1883-1957), Nobel Prize for Literature, who commemorated his people’s struggle for freedom in his novels.

Today, the monastery is actually a national shrine. Built in 1587 in the Venetian style the convent has been partially rebuilt. There is also a small memorial with busts of Abbot Gavriil and Kapetan Kostas Giamboudakis and a woman who is said to have fought particularly brave.

The inner courtyard of the monastery.

You can also visit an ossuary in a chapel, in which skulls with cuts and gunshot wounds are exhibited, silent witnesses of the massacre carried out by the soldiers before the detainees blew themselves up in the powder magazine. The monastery itself is easily accessible from Rethymnon via the National road to Heraklion.

„The Battle of Crete“. More on our website www.radio-kreta.de.