The Cretan soul.

What does it mean to be Cretan?

And what does being Cretan have to do with the strange Greek word „Kouzoulada“, which describes a combination of craziness and passion unique to this island?

Thoughtful insights into the Cretan soul by Nikos Psilakis. Translated and enhanced by us.

Shortly before midnight at the Venetian fountain in the heart of the city, four young men walk by arm in arm singing. They wear jeans and button-down shirts; two wear black shirts, the color of mourning. They are obviously villagers visiting the city.

A couple of surprised tourists try to catch them with their cell phone cameras; others pass by indifferently. It’s a familiar sight for the locals. A little further down, on the street leading to the harbor, there are street musicians with drums and guitars in front of crowded bars playing a mix of all kinds of international music. The city buzzes with life. It is Irakleio – Heraklion. It could also be Chania, Rethymno or Agios Nikolaos. Changing is only the name, never the soul.

Of course, there are differences, but wherever you go you will be surprised by the phenomenon of “Crete” which you will find in abundance everywhere, even in very small details.

The young men set off, sing and disappear in the narrow side streets. The echo of their songs still reaches our ears. They seem to be endless in time and tell about love, forbidden love – and about unbearable separation: „How should I split from you and go? How am I supposed to live without you when we separate? “

The same verses can be heard on this island for more than three centuries. It’s a favorite song, a kind of weird local anthem deriving from an old epic by Vitsentzos Kornaros, a man with Venetian ancestors who grew up in the traditions of Crete. It is written in the early 17th century in the island’s dialect which is still spoken today. Until today it doesn’t really have a melody to dance to.

My grandfather, although illiterate, knew the whole epic by heart. All he could write was his name, with which he had to sign during the last uprising of the 19th century when imprisoned. Whenever he was holding a pen it seemed to me that he was holding a gun. Maybe he had the same feeling …

Often he put his beloved on a horse and rode six hours from a village with her through the plains to his mountain hiding places, and he sang this epic to her. Always the same song, no matter how many times they went the same way, he sang it, coming and going. The horse was decorated in a ceremonial style, with a woven blanket on the saddle – that was how people traveled those days – it was a sign of the nobility. The hours passed, but the song went on. With 10,000 rhyming Iambian verses – how could you ever reach the end?

This song is called Erotokritos. A chivalric novel in verse form, packed with dialogues – one of the great epic poems of European literary tradition. Unfortunately, it is little known outside of Greece because of its linguistic peculiarities. A language full of charm and feeling, it is extremely difficult to translate.

What were these young men doing and thinking as they wandered the streets that night singing this song? Maybe they were doing exactly the same my grandfather – a lifelong revolutionary – was doing when he sang this song on his horse. A whole century separates these two – and a song unites them.

There may not be a single Cretan today who does not know at least a handful of these lines, who at some point did not sing them. It is sung in the company of friends, it is available on CD and on the Internet and it is almost always heard on festivals and celebrations, accompanied by the lyre, the local string instrument.

Why Erotokritos? The answer is provided by the text itself, which is full of love and war and tells about discords and serenity, serenades in front of windows and the sound of swords. It is about fights and deadly competitions, but also about tender words. It is a true hymn to beauty, passion, love – a hymn to life itself, sprinkled with distilats of popular wisdom.

This song is merely a picture of Crete itself.

A few years ago I found myself at a village festival in the foothills of the western region of Rethymno. It was April 23, the day of St. George, Patron Saint of the mountain people. Cheeses piled up in front of the church – shepherd’s sacrifices which the priest would divide and offer to the crowd.

Shortly before, village boys on horseback had carried an icon of the Saint through the streets. They were all in local costumes, the type of clothing unusual to be worn today and if mainly in order to promote the local identity. The procession went through all the streets of the village.

A stream of people followed this Byzantine icon depicting the Saint as a young man: strong, handsome and armed, reaching out for his bloody lance.

When the procession was over, young men gathered next to the church, there were probably 15 or 20 people, and started singing. In this case, they did not sing the Erotokritos; they sang the Rizitika, ancient songs, the authentic voices of the Cretans living in the mountains where the lives were short in the badlands of history.

The songs are simple, austere, robust – a kind of Byzantium’s echo existing only to manifest their own existence. The songs speak of freedom, love and pain – perhaps the best picture of the mentality of the Cretans whose identities are shaped with the mosaic stones of their long history.

Today, in the early decades of the 21st century, many groups of young people in western Crete meet two or three times a week to sing the Rizitika and learn new songs. How has all this survived through time? My answer to this question was to start writing about the Cretans with a song.

From one end to the other, the island fascinates by its contrasts: high, jagged mountains and cosmopolitan beaches. Crete is the great journey of history, it is living together with others, and it is friendship and conflicts, conflicts that have led to great uprisings. The creator of the cosmos has placed this island between three continents. Africa and Asia are only a short sea journey away. But Crete remains an island, sealed in its own world.

When I talk about Crete I always think of its landscape; peaceful, calm and yet wild. And I remember a deceased friend, the archaeologist Yannis Sakellarakis, who told the story of how he could put all four seasons into a single day. He arrived on the island one morning with a group of young archeology students. They went for a walk, ate bougatsa (pudding cake) on the square and got on the bus to Ida. Their destination was the mythical cave in which Zeus, the king of the gods, is said to have been created.

It was April. Snow covered the entrance to the cave and the cold was acrid. It was still winter on the mountain slopes – there are years when the snow extends until August up there. This sounds unusual for a Mediterranean landscape bathing in the sunlight, but Crete has three mountains, the peaks of which are almost 2,500 meters high.

On the way back to the plain, the bus was stopped by two shepherds who had just milked their sheep and were preparing to make cheese. Everybody was asked to get off the bus, and the students watched the milk being boiled in large kettles just as it was done thousands of years ago on the same mountain. In the end, the students were offered fresh steaming myzithra, a whey cheese. Hospitality, the famous Filoxenia, means sharing what you have with strangers – this is an unwritten law in Crete.

But the trip wasn’t over yet. Shortly afterwards we found ourselves in a meadow with countless narcissus plants – called Manousakia in Crete. They were in full bloom and peeked out between the bushes; white blossoms like the snow the travellers had been holding in their hands just a little while ago.

„Crete the island inside you“.

In the Messara Plains

It was afternoon when they reached the Messara Plains. Here they found a completely different landscape: endless fields with strawberries, bright red and fragrant. Another opportunity for enjoying Cretan hospitality: The delightful berries were accompanied by Raki, Crete’s local spirit and most famous drink.

The last stop of the day was Matala, a small port in the south, once a poor fishing village, then a paradise for hippies and now simply a tourist destination full of souvenir shops. The sea was crystal clear, no waves in sight. The beaches stretch under old tombs and caves where once the hippies lived.

Who could resist a swim in the warm Libyan Sea?

One of the students looked at his watch: „Two and a half hours ago I was shivering from the cold in the snow!“

I have to talk about the landscape because I believe that it also shaped the Cretan soul. The country on Crete is rough, and calm, and gentle at the same time. This is a place where tradition first becomes law only to be broken shortly after.

My colleagues are honest, upright and unruly: with their native dances, which are still popular today, with their songs, with the rifles with which they shoot in the air to express their irrepressible joy, and with their famous Cretan knives, symbols of the island, decorated with intricate patterns, – and with their love songs. To date, these knives belong to the most important local folk art, which to my opinion reflects the contemporary Crete.

Another one is the „Katsouna“, a shepherd’s stick with a curved handle made of hard, gnarled wood which aesthetically looks as postmodern as grotesque. It is a symbol of an agricultural and pastoral past, and young people rarely use it. This walking stick was a necessary companion for farmers and shepherds alike who can use it as a weapon on long walks and in conflict situations.

Only in recent years it has become a symbol of the local identity – an expression of Cretan masculinity. Now, katsounas can be found everywhere; in shops selling local goods and folk art, in street stalls where they are sold directly from the producers, at farmers‘ markets and even in grocery stores. They are used at protests and demonstrations – and are an object of fame on the front pages of newspapers.

Young farmers are proud to pose with their katsounas.

Agriculture is still the basis of the local economy. The gray-green olive trees are everywhere. Crete is perhaps the most densely planted olive grove in the world. But there are also vineyards, gardens, greenhouses and small orchards. Cretans are proud of their products, including olive oil, honey, cheese, wine and rusks – they constitute the „Cretan” diet.

Last year I was in a farmhouse where I was offered homemade wine. I took the first glass. When my hosts saw that I was hesitating, they said, „But it is holy water!“ That it is, the best in the world.

There are indeed amazing wines produced in Crete. Of course, their own unrefined wine was not one of the best. They knew it and I knew it, too.

And I like their pride.

What would Crete be without exaggeration? How would these people be? Were not all the great moments in history moments of exaggeration? From isolated revolutionaries who fought regular army forces to the men and women of 1941 who used their katsounas and pickaxes against German paratroopers and fought against aircrafts and machine guns? These sticks were not just an extension of their hands – they were an extension of their souls. The weight of tradition counted more than the laws of cold logic. Centuries and centuries of Cretan defiance had taught them.

Since the beginning of the 20th century, when the excavations by Minos Kalokairinos and Arthur Evans brought the history of the Minoan civilization to light, names from the world of myths have entered the life of the island irrevocably. Minos, Ariadne, Knossos, Phaistos, Kydonia, Europa and Gortyna are the names of ships, restaurants, taverns and small and large companies.

The word „Minoan“ is often used on goods and services of all kinds.

A few decades ago, some scholars thought of reviving Minoan architecture. They never really made it. Nevertheless, „Minoan“ columns can be found in a striking terracotta color in many hotels. Houses in villages and towns on the island mimic the architectural forms that Evans discovered – by this reinventing Knossos according to their tastes.

Crete today is an important tourist destination. The changes the island has gone through are so drastic that it changed the landscape itself. A Cretan from 1940 or 1950 would not even recognize the beaches on the north shore of the island today. At that time they were deserted. Now, they’re full of tourists, more than you ever thought possible.

Yet, a hypothetical time traveler would still feel at home when visiting a local festival or social event like a wedding. Changes are slower in these traditions. The entertainment points may have changed, but the way people celebrate is the same.

In the past, all celebrations including weddings and baptisms took place in the village squares. Today, they take place in huge halls accommodating hundreds, maybe even thousands, of guests. But they still include the Cretan lyre, local dances and songs.

If you want to discover the soul of Crete today, you will not find it on these crowded beaches or their immediate vicinity. Because it is in the mountains, in the villages, in wine, in honey, in oil and of course, in the people themselves – far away from the summer tourist hype.

I often ask myself what Crete actually is.

An old monk told me a story a couple of years ago which probably illustrates the Cretan soul best: A shepherd came to his monastery one evening before dark. The monk didn’t recognize him, but he saw the man putting a considerable bill into the collection box and prayed in front of every icon, from the smallest to the largest. A few days later he saw the man’s photo in the newspaper. He had been caught red-handed stealing a sheep, a crime that plagued Crete for eons. In the monastery he had sought the help of the saints to commit this illegal act.

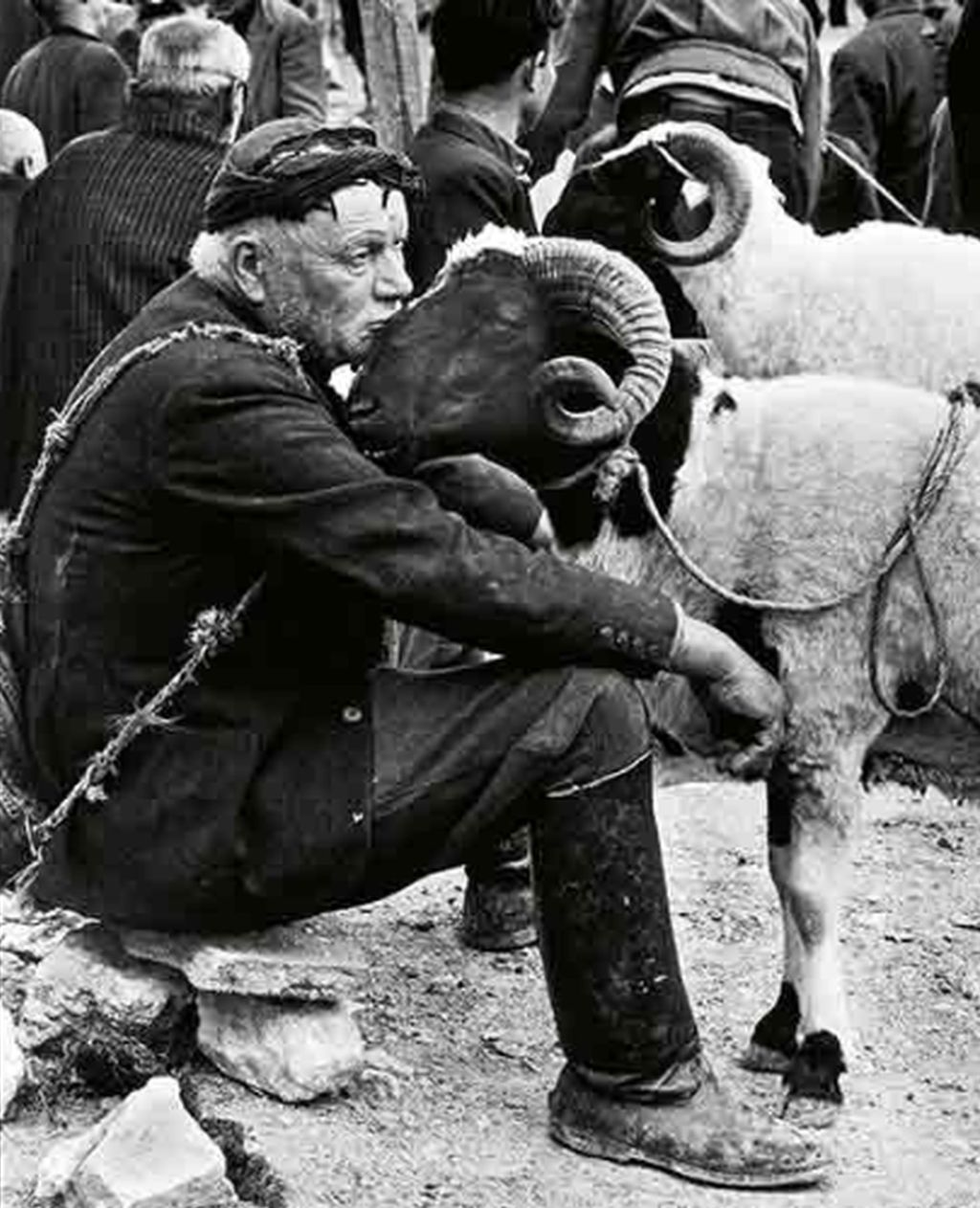

Crete is reflected in this idiomatic word – „Kouzoulada“ – which I assume that anyone who did not grow up in Crete would have difficulty understanding it. Some people translate it as madness, insanity, but that’s not really true. I prefer to call it passion, excess. Abundance in love and in war, in serenity and in the storm, in pride and anger, in joy and suffering.

What would Crete be without its Cretans?

It would surely be a beautiful place, but there would be no festivals, no voices raising in songs, no dances, no „Erotokritos“, no weapons fired into the air in wild and passionate joy, no „katsounas“, no knives , I think there would be no “Kouzoulada”.

And that would be a real shame !!!